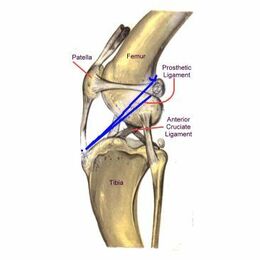

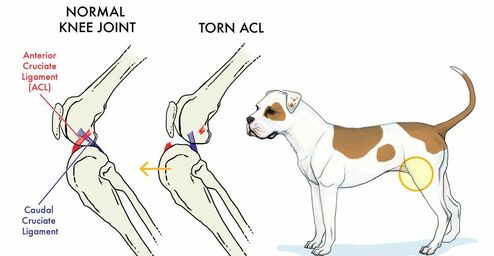

| The knee is a fairly complex joint. It consists of the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (calf bone), the patella (kneecap), and the bean-like fabellae behind. There are chunks of cartilage in between the femur and tibia called the medial and lateral menisci. They act like cushions, and an assortment of ligaments holds everything together, allowing the knee to bend the way it should and keep it from bending the way it shouldn't. There are two cruciate ligaments that cross inside the knee joint: the cranial (in people the anterior) cruciate and the caudal (in people, the posterior) cruciate. People may be familiar with the term ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) and sporting injuries. They connect from one side of the femur on top to the opposite side of the tibia on the bottom, the two ligaments forming a cross or an X (hence the name cruciate) inside the knee joint. The anterior/cranial cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from slipping forward out from under the femur. When the cranial cruciate ligament ruptures, the knee starts to slip - see video below | A normal knee |

| How can I tell if my dog's knee is injured? The ruptured cruciate ligament is the most common knee injury of dogs. In fact, there is a strong chance that any dog with sudden hind leg lameness has a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament rather than something else. Often owners find that in some instances the hind leg suddenly gets so sore that the dog can hardly bear weight on it. If left alone, it will appear to improve over the course of a week or two but the knee will be notably swollen and arthritis will set in quickly. The key to the diagnosis of the ruptured cruciate ligament is the demonstration of an abnormal knee motion called a drawer sign. It is not possible for a normal knee to show this sign. This is shown on the 2nd video clip. | A knee with a complete rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament |

What Happens if the Cruciate Rupture is Not Surgically Repaired

Without a fully intact cruciate ligament, the knee is unstable. Wear between the bones and meniscal cartilage becomes abnormal and the joint begins to develop degenerative changes. Bone spurs called osteophytes develop resulting in chronic pain and loss of joint motion. This process can be arrested or slowed by surgery but cannot be reversed.

Without a fully intact cruciate ligament, the knee is unstable. Wear between the bones and meniscal cartilage becomes abnormal and the joint begins to develop degenerative changes. Bone spurs called osteophytes develop resulting in chronic pain and loss of joint motion. This process can be arrested or slowed by surgery but cannot be reversed.

- Osteophytes are evident as soon as 1 to 3 weeks after the rupture in some patients. This kind of joint disease is substantially more difficult for a large breed dog to bear, though all dogs will ultimately show degenerative changes. Typically, after several weeks from the time of the acute injury, the dog may appear to get better but is not likely to become permanently normal.

- In one study, a group of dogs was studied for 6 months after cruciate rupture. At the end of 6 months, 85% of dogs less than 15 kg of body weight had regained near normal or improved function while only 19% of dogs over 15 kg had regained near normal function. Both groups of dogs required at least 4 months to show maximum improvement.

What Happens in Surgical Repair?

There are three different surgical repair techniques commonly used today.

Extracapsular Repair

This procedure represents the traditional surgical repair for the cruciate rupture. This surgery creates an artificial ligament on the outside. This used to be the main repair performed, but it is now known that no matter what material is used, the ligament loosens within 2 months.

For this procedure first, the knee joint is opened and inspected. This is essential for every knee surgery. The torn or partly torn cruciate ligament is removed. Any bone spurs of significant size are bitten away with an instrument called a rongeur. If the meniscus is torn, the damaged portion is removed. A large, strong suture is passed around the fabella behind the knee and through a hole drilled in the front of the tibia. This tightens the joint to prevent the drawer motion, effectively taking over the job of the cruciate ligament.

There are three different surgical repair techniques commonly used today.

Extracapsular Repair

This procedure represents the traditional surgical repair for the cruciate rupture. This surgery creates an artificial ligament on the outside. This used to be the main repair performed, but it is now known that no matter what material is used, the ligament loosens within 2 months.

For this procedure first, the knee joint is opened and inspected. This is essential for every knee surgery. The torn or partly torn cruciate ligament is removed. Any bone spurs of significant size are bitten away with an instrument called a rongeur. If the meniscus is torn, the damaged portion is removed. A large, strong suture is passed around the fabella behind the knee and through a hole drilled in the front of the tibia. This tightens the joint to prevent the drawer motion, effectively taking over the job of the cruciate ligament.

- Typically, the dog may carry the leg up for a good two weeks after surgery but will increase knee use over the next 2 months eventually returning to normal.

- Typically, the dog will require 8 to 12 weeks of exercise restriction after surgery (no running, outside on a leash only including the backyard.

- The suture placed will loosen and break 2 to 12 months after surgery and the dog's own healed tissue will hold the knee.

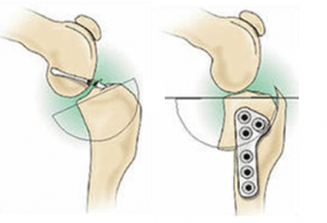

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)

This procedure uses a fresh approach to the biomechanics of the knee joint and was developed with larger breed dogs in mind. Now we know this is the preferred surgery for both large and small breed dogs. This is the only procedure to significantly reduce the progression of arthritis in the majority of dogs when compared to extracapsular and TTA.

The procedure changes the angle at which the femur bears weight on the flat "plateau" of the tibia. The tibia is cut and rotated in such a way that the natural weight-bearing of the dog actually stabilizes the knee joint. As before the knee joint still must be opened and damaged meniscus removed. The cruciate ligament remnants may or may not be removed depending on the degree of damage.

This surgery is complex and involves special training in this specific technique. Many radiographs are necessary to calculate the angle of the osteotomy (the cut in the tibia). This procedure typically costs more than the extracapsular repair as it is more invasive to the joint but it is far superior.

Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA)

The TTA similarly uses the biomechanics of the knee to create stability though this procedure changes the angle of the patellar ligament. This is done by cutting and repositioning the tibial crest where the patellar ligament attaches and implanting a titanium or steel "cage," "fork," and plate as well as bone grafts to stabilize the new angle. Like the TPLO, bone is cut, special equipment is needed including metal implant plates. Similar recoveries are seen relative to the TPLO but it does not slow down the progression of arthritis as well as the TPLOs.

Which Procedure is Better?

The TTA and TPLO are much more invasive, more expensive, and require special equipment and specially trained personnel. They also have greater potential for complication. Are they worth it? For all the theory behind extracapsular, TPLO and TTA, results one year post-operative seem to be the same regardless of which of the three procedures the dog had performed. However, the progression of arthritis in the extracapsular technique and the TTA is rapid compared to the TPLO. The health of the joint with a TPLO will be far better than the other techniques. There is some evidence that recovery to normal function may be faster with the TPLO.

This procedure uses a fresh approach to the biomechanics of the knee joint and was developed with larger breed dogs in mind. Now we know this is the preferred surgery for both large and small breed dogs. This is the only procedure to significantly reduce the progression of arthritis in the majority of dogs when compared to extracapsular and TTA.

The procedure changes the angle at which the femur bears weight on the flat "plateau" of the tibia. The tibia is cut and rotated in such a way that the natural weight-bearing of the dog actually stabilizes the knee joint. As before the knee joint still must be opened and damaged meniscus removed. The cruciate ligament remnants may or may not be removed depending on the degree of damage.

This surgery is complex and involves special training in this specific technique. Many radiographs are necessary to calculate the angle of the osteotomy (the cut in the tibia). This procedure typically costs more than the extracapsular repair as it is more invasive to the joint but it is far superior.

- Typically, most dogs are touching their toes to the ground by 10 days after surgery although it can take up to 3 weeks.

- As with other techniques, 8-12 weeks of exercise restriction are needed.

- Full function is generally achieved 3 to 4 months after surgery and the dog may return to normal activity.

- Athletic dogs will have the greatest outcomes achieved with this surgery

Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA)

The TTA similarly uses the biomechanics of the knee to create stability though this procedure changes the angle of the patellar ligament. This is done by cutting and repositioning the tibial crest where the patellar ligament attaches and implanting a titanium or steel "cage," "fork," and plate as well as bone grafts to stabilize the new angle. Like the TPLO, bone is cut, special equipment is needed including metal implant plates. Similar recoveries are seen relative to the TPLO but it does not slow down the progression of arthritis as well as the TPLOs.

Which Procedure is Better?

The TTA and TPLO are much more invasive, more expensive, and require special equipment and specially trained personnel. They also have greater potential for complication. Are they worth it? For all the theory behind extracapsular, TPLO and TTA, results one year post-operative seem to be the same regardless of which of the three procedures the dog had performed. However, the progression of arthritis in the extracapsular technique and the TTA is rapid compared to the TPLO. The health of the joint with a TPLO will be far better than the other techniques. There is some evidence that recovery to normal function may be faster with the TPLO.

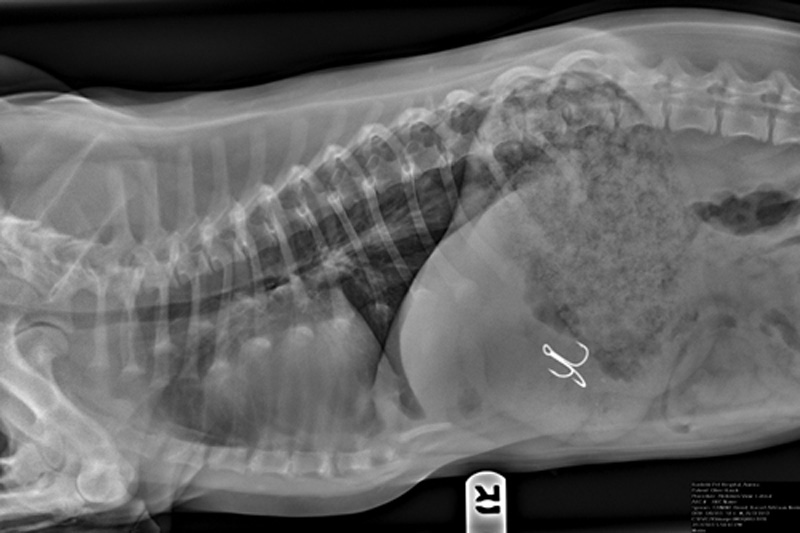

How is the TPLO performed?

| Before surgery, an x-ray of the stifle is taken to measure the angle at the top of the shin bone, called the tibial plateau angle. The goal of the surgery is to reduce this angle so that dynamic joint instability (cranial tibial thrust) is eliminated. This is usually accomplished by creating a post-surgical angle of between 4 and 10 degrees, an angle not much different than is found in the human knee. In most cases the surgical procedure starts with an exploration of the inside of the stifle joint. This can be done arthroscopically or with open joint surgery. The purpose is to assess the meniscal cartilages for any possible damage. Damaged cartilage must be removed if the dog is to regain normal pain-free function. The TPLO procedure itself involves the use of a curved saw blade to make a curved cut on the inside, or medial, surface of the top of the tibia. The cut top portion is then rotated to create the desired tibial plateau angle. A stainless steel bone plate is then placed on the bone to hold the two pieces in their new alignment. Now that you know a bit about TPLO, let’s review some questions about the procedure. |

Q: Does My Dog Really Need Surgery? I Read That They’ll Do Just Fine Without Surgery.

A: Published data suggest that approximately 15% of dogs will recover reasonably good clinical function without surgery. Most of those dogs will be small breeds, under 7 to 10kg of body weight. Those that recover normal function tend to do so within 4-6 weeks after they first become lame. For the majority of dogs, surgery is the only way to return them to good function, period…..not braces or medications or herbs or physical therapy or wishing or hoping!

Q: Which Patients Will Benefit From TPLO?

A: While the procedure can be performed on just about any patient, including small dogs and cats, TPLO seems to be most applicable to larger breed, active dogs. Although some surgeons have differing opinions, most feel that smaller dogs will do equally well regardless of what procedure is performed. In general, dogs weighing over 45 pounds (20 kg), especially if they are very active, will benefit the most from TPLO.

Q: Why Is TPLO So Costly, Especially When Compared To Other Cruciate Repair Surgeries?

A: TPLO requires specialized equipment including a motorized bone saw with a specially-designed curved blade, a surgical stainless steel bone plate and 6-9 bone screws, between 4-6 x-rays, a significant investment in training on the part of the surgeon, and up to 2-4 hours of preparation, surgical and recovery time for each patient.

Q: What Aftercare Is Required?

A: Individual surgeons approach this differently and there is no hard evidence to suggest what is best. Some restrict post-operative patients from climbing stairs and encourage kenneling when the owners are not home to supervise their pet. Others encourage leash walks and moderate exercise under the owner’s control. Still others advocate active physical rehabilitation beginning immediately after surgery. All will require follow-up x-rays at various stages to gauge healing of the cut in the bone. Once bone healing is complete, then exercise can be gradually increased to normal.

Q: What About Possible Complications?

A: TPLO is a major surgery and complications are possible. Published reports suggest the complication rates may be somewhat higher than with less invasive surgeries, but other factors may be involved including patient factors and surgeon experience with the procedure. Most complications are minor in nature in that they can be resolved without additional surgery and have an ultimately successful outcome. Included in this category would be things like infections and inflammation of the patellar tendon. More major complications, including failure of plates or screws and fracture of the tibia or fibula, are uncommon. The development of bone cancer many months or years later in the area of the surgery has been noted in a small number of TPLO dogs. The possible connection of this cancer with the procedure is highly controversial as the top portion of the tibia is a common location for bone cancer in the dog even when no surgery or cruciate problem is a factor. Whether the rate of such cancers in TPLO dogs is higher than normal is not clear. One of the most common post-operative complications is not directly related to the TPLO procedure. Tears of the meniscal cartilage in the stifle are a common consequence of an unstable joint. Such tears may exist at the time of surgery and they can develop in up to 11% of patients after surgery. That’s true in dogs and humans regardless of what kind of surgery they undergo. Typically, these patients do well for weeks or months after surgery before suddenly becoming lame again.

Q: Is TPLO Really Better Than Other Surgical Options?

A: If your dog is larger, younger and active the answer is yes. The data has not always been conclusive about this, however. For a good part of the first 20-25 years after the development of TPLO, surgeons were faced with a paradox: they were seeing significantly better results with TPLO than with other procedures they had used in large dogs….but the research data wasn’t backing up these observations. Why? Undoubtedly, Dr. Barclay Slocum’s decision to restrict availability of the procedure through patenting of the technique and equipment had a major effect on the amount of research that was done.

In addition, one must realize that veterinary research is always more restricted in scope and numbers than is seen in human medicine. The New England Journal of Medicine will commonly publish studies involving tens or hundreds of thousands of human test subjects. In veterinary medicine a study of 50 animals is a big study! Why? Money. The difference in available research funds between human and veterinary medicine is astronomical, which probably isn’t surprising. In the last few years, the research data is starting to confirm what surgeons have known all along: TPLO dogs return to function faster, they develop less joint arthritis, and they tend to return to better functional levels than is seen with other techniques. Evidence is now showing that the long term outcomes are better than the TTA technique and Extracapsular repair. Although we can’t say for certain, it appears that these positive results also apply to other similar techniques such as CWO, CBLO and TTO.

A: Published data suggest that approximately 15% of dogs will recover reasonably good clinical function without surgery. Most of those dogs will be small breeds, under 7 to 10kg of body weight. Those that recover normal function tend to do so within 4-6 weeks after they first become lame. For the majority of dogs, surgery is the only way to return them to good function, period…..not braces or medications or herbs or physical therapy or wishing or hoping!

Q: Which Patients Will Benefit From TPLO?

A: While the procedure can be performed on just about any patient, including small dogs and cats, TPLO seems to be most applicable to larger breed, active dogs. Although some surgeons have differing opinions, most feel that smaller dogs will do equally well regardless of what procedure is performed. In general, dogs weighing over 45 pounds (20 kg), especially if they are very active, will benefit the most from TPLO.

Q: Why Is TPLO So Costly, Especially When Compared To Other Cruciate Repair Surgeries?

A: TPLO requires specialized equipment including a motorized bone saw with a specially-designed curved blade, a surgical stainless steel bone plate and 6-9 bone screws, between 4-6 x-rays, a significant investment in training on the part of the surgeon, and up to 2-4 hours of preparation, surgical and recovery time for each patient.

Q: What Aftercare Is Required?

A: Individual surgeons approach this differently and there is no hard evidence to suggest what is best. Some restrict post-operative patients from climbing stairs and encourage kenneling when the owners are not home to supervise their pet. Others encourage leash walks and moderate exercise under the owner’s control. Still others advocate active physical rehabilitation beginning immediately after surgery. All will require follow-up x-rays at various stages to gauge healing of the cut in the bone. Once bone healing is complete, then exercise can be gradually increased to normal.

Q: What About Possible Complications?

A: TPLO is a major surgery and complications are possible. Published reports suggest the complication rates may be somewhat higher than with less invasive surgeries, but other factors may be involved including patient factors and surgeon experience with the procedure. Most complications are minor in nature in that they can be resolved without additional surgery and have an ultimately successful outcome. Included in this category would be things like infections and inflammation of the patellar tendon. More major complications, including failure of plates or screws and fracture of the tibia or fibula, are uncommon. The development of bone cancer many months or years later in the area of the surgery has been noted in a small number of TPLO dogs. The possible connection of this cancer with the procedure is highly controversial as the top portion of the tibia is a common location for bone cancer in the dog even when no surgery or cruciate problem is a factor. Whether the rate of such cancers in TPLO dogs is higher than normal is not clear. One of the most common post-operative complications is not directly related to the TPLO procedure. Tears of the meniscal cartilage in the stifle are a common consequence of an unstable joint. Such tears may exist at the time of surgery and they can develop in up to 11% of patients after surgery. That’s true in dogs and humans regardless of what kind of surgery they undergo. Typically, these patients do well for weeks or months after surgery before suddenly becoming lame again.

Q: Is TPLO Really Better Than Other Surgical Options?

A: If your dog is larger, younger and active the answer is yes. The data has not always been conclusive about this, however. For a good part of the first 20-25 years after the development of TPLO, surgeons were faced with a paradox: they were seeing significantly better results with TPLO than with other procedures they had used in large dogs….but the research data wasn’t backing up these observations. Why? Undoubtedly, Dr. Barclay Slocum’s decision to restrict availability of the procedure through patenting of the technique and equipment had a major effect on the amount of research that was done.

In addition, one must realize that veterinary research is always more restricted in scope and numbers than is seen in human medicine. The New England Journal of Medicine will commonly publish studies involving tens or hundreds of thousands of human test subjects. In veterinary medicine a study of 50 animals is a big study! Why? Money. The difference in available research funds between human and veterinary medicine is astronomical, which probably isn’t surprising. In the last few years, the research data is starting to confirm what surgeons have known all along: TPLO dogs return to function faster, they develop less joint arthritis, and they tend to return to better functional levels than is seen with other techniques. Evidence is now showing that the long term outcomes are better than the TTA technique and Extracapsular repair. Although we can’t say for certain, it appears that these positive results also apply to other similar techniques such as CWO, CBLO and TTO.

Updated 27/12/2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed